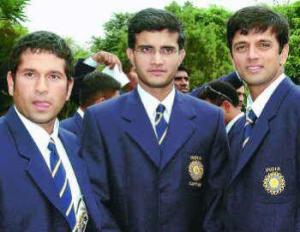

IS there anyone, no matter how experienced, how qualified, how seasoned, who dare to measure the greatness that lies within Sachin Tendulkar? I doubt it. In an era of sublime batsmen - Lara, Kallis, Dravid and Ganguly, the Australian top five, none of whom need to have their names spelt out -Sachin has no equal.For 13 years Test and one-day batsmanship has been defined by his deeds. We have been in awe of his skills, ready first of all to be enchanted by his youth, then to be respectful of his mighty figures, and now to be assured that, whatever Bradman achieved, whatever Gavaskar did, Tendulkar stands on his own.He is not just the richest of cricketers but the most richly rewarding to watch.

IS there anyone, no matter how experienced, how qualified, how seasoned, who dare to measure the greatness that lies within Sachin Tendulkar? I doubt it. In an era of sublime batsmen - Lara, Kallis, Dravid and Ganguly, the Australian top five, none of whom need to have their names spelt out -Sachin has no equal.For 13 years Test and one-day batsmanship has been defined by his deeds. We have been in awe of his skills, ready first of all to be enchanted by his youth, then to be respectful of his mighty figures, and now to be assured that, whatever Bradman achieved, whatever Gavaskar did, Tendulkar stands on his own.He is not just the richest of cricketers but the most richly rewarding to watch.In the early 21st century we can easily recall the achievements of another generation only recently past: Lloyd and Richards, the Chappell brothers, Martin Crowe, Javed Miandad, Gower and Botham, Azharuddin and Zaheer Abbas; all touched with angelic grace and producing figures to astound us. None measure up to the prowess of Tendulkar, the supreme batsman. We knew it when the World Cup began and now we have had all our adjectives confirmed, all our dreams realised, seen his muscular batsmanship reach heights we only guessed at, seen, best of all, his courage, his imaginative use of the unorthodox, and wondered once again at his pocket battleship strength. Here is no Viv Richards using his boxer's power to whip the ball to whatever part of the field took his fancy; here is no David Gower, harnessing his lithesome elegance and timing to ease the ball hither and thither.

For, let us make no bones about it, Tendulkar is small yet, like those Amazons of the tennis circuit Venus and Serena Williams, he can stand away from the ball and yet hit it powerfully. Into the crowd as he did against Pakistan in that never-to-be-forgotten win or around the boundary ropes as he did in the England game. There has never been another batsman like him. One of a kind; and what a one! The poet Chesterton's phrase "The legend of an epic hour'' from The Napoleon of Notting Hill fits him precisely. Tendulkar is more properly The Napoleon of Centurion, a ground that ought to have a memorial to his deeds but before he raced to that magic score against Pakistan he had already made this tournament his own. He seems to have realised quicker than most that the old tactic of a 15-over bash at the top of the innings would not apply against the white ball on these sluggish South African pitches.

Sixty runs has been the mean average for the overs of field restriction in this event and that is how Sachin went about scoring his runs. How right he was too.By the time the preliminary matches had been completed, after 24 days of controversy and confusion, Tendulkar stood head and shoulders above the rest. Remember Shane Warne's departure under the shadow of a drugs charge, Rashid Latif's threat to sue, New Zealand's decision to drop out of the match in Nairobi, England's long battle to have their Zimbabwe match moved to South Africa, arguments about the failure to post four fielders in the ring, the ban on Waqar Younis for bowling beamers, Pakistan's fight during a football game, South Africa's inability to interpret the Duckworth-Lewis rules. The stories are endless. Happily, they are all forced into the shadow by Tendulkar's dynamic batting. As the preliminary matches ended his statistics took the breath away.

He began on the fourth day of the World Cup with 52 from 72 balls off Holland; a pipe-opener that went almost unnoticed as the host South Africa led by Shann Pollock slaughtered Kenya. (If only we had known then that Kenya were not the mugs of the competition but the first round heroes; would we not at this moment be sitting on our own Caribbean island, soaking up the sun and wondering how we might spend our ill-gotten gains.)

From that moment he made a steady progress of sizeable scores: 36 off 59 against Australia, 81 off 91 against Zimbabwe, 152 off 151 versus Namibia, 50 from 52 against England and finally, gloriously, 98 from 78 balls delivered by Pakistani bowlers brought victory and a certain place in the Super Sixes. In total six innings, 469 runs, at 78.19 with a century and four fifties ? not to mention a strike rate of 93.80 ? meant that as the teams regrouped for the next stage it was being called Tendulkar's Tournament. When we set his last few weeks in context we are not disappointed. Overall in World Cups Tendulkar has played 27 innings in 28 matches, been not out three times and scored 1,528 runs with that 152 not out against hapless Namibia his highest score. He averages a colossal 63.67, he scores at 88.63 for each 100 balls he faces and he has four hundreds and 10 fifties.

Surely there is another World Cup in his life which means that one day he will retire - yes, even gods have to put their feet up at some stage in their lives ? with figures beyond the dreams of youngsters starting on their one-day careers. Just as a reminder, Tendulkar has played 309 one-day games, batted 300 times, scored 12,015 runs with his highest score an undefeated 186, an average of 44.50, 34 centuries and 60 fifties. He collects those runs at 86.43 runs each 100 deliveries. I will throw in his Test statistics just to show what a big man lies inside that chunky body. In 105 Tests he has batted 169 times, scored 8,811 runs, including 31 centuries and 35 fifties at an average of 57.59.

So as the preliminary matches in the 2003 World Cup ended, Tendulkar had scored 20826 international runs and 65 international centuries and, not just in the opinion of the sub-continent, was sitting so high on Mount Everest that his rivals appeared to be making their way through the foothills. And, even in this World Cup, there is so much more to come. Perhaps even success for India if the rest of the side can back up that great man's towering success. The figures are not as impressive but he bowls and fields as enthusiastically as he must have done in his teen years when he set out on this great career in the rough grounds of Mumbai. He has captained India too and one day he may do so again.

So thank heavens for Tendulkar. He may be a millionaire many times over and he might, if he chose, retire and live in luxury for the rest of his days.But the best of this extraordinary cricketer is that, having played all the matches on the calendar, he rises every morning keen to play, looking forward to carrying that hefty bat to the middle and certain, as he has every right to be, that he can make even more runs.